Foal Management

Page 09 /

Similar to other neonatal animals, foals are at high-risk of developing infectious and non-infectious conditions shortly after birth. Careful and consistent management is critical to prevent these conditions from developing.

In this FAAST review, we will cover:

Management of the Pregnant Mare

Condition

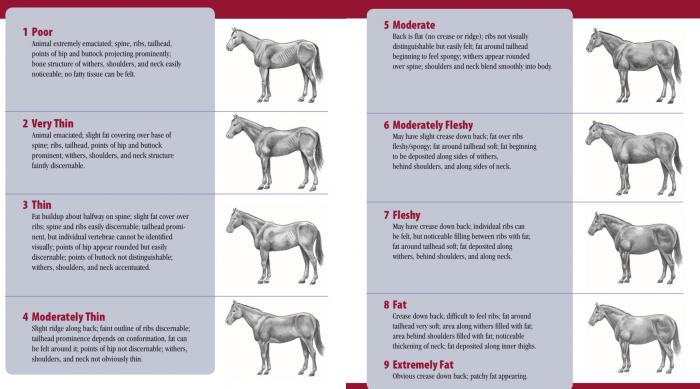

One of the major challenges in breeding programs is ensuring that mares maintain optimal body condition in pregnancy and through lactation. This requires careful consideration of the mare’s energy needs. The target is achieving an appropriate energy balance, where pregnant mares are not losing or gaining significant amounts of weight.

Underfeeding/Disease: When mares have a sudden loss of weight, which could be due to underfeeding or disease, it can lead to a reduced foal weight and affect the mare’s colostrum quality and milk yield, which increases the risk of disease.

Overfeeding: Can lead to poorer colostrum quality in mares. It will also lead to a more difficult foaling as well due to fat buildup in the birth canal of the mare. Pregnant mares should not exceed a body condition score of 7.5 out of 9, Ideally, they should foal with a body condition score of 6-7 (moderately fleshy-fleshy) so as not to drop below 5 during lactation.

Source: Science Equine

Supplements

Supplementation with selenium and vitamin E in late gestation has been proven to be successful in promoting transfer of colostrum. Copper supplementation in late pregnancy can also help to ensure healthy skeleton development of foals1.

Work with your veterinarian and/or nutritionist to ensure body condition score is optimal throughout pregnancy and the supplementation of certain minerals and vitamins occur to improve foal health

Vaccination

Mares should be vaccinated against disease in late pregnancy to enhance colostrum quality. Specifically, Rotavirus A is one specific pathogen that is a major cause of diarrhea and is a highly contagious disease in young foals. To improve the quality of colostrum against rotavirus A, mares can be vaccinated at 8, 9, and 10 months of gestation2. This will help to protect the young foals against rotavirus if combined with excellent colostrum management.

Work with your veterinarian to develop a vaccination protocol and schedule to ensure that the herd is vaccinated against any diseases of concern

Foaling Management

Complications occurring at birth are a risk factor for the development of disease in foals. Being prepared and carefully monitoring the mare in the lead-up to foaling is important to ensure if an intervention is needed, and that it is provided at the right time.

Monitoring

The most common way to predict the onset of foaling is to start looking for conformational changes occurring around 335 days after the last breeding. Changes in the development of the mammary gland (udder enlargement and waxing) are reliable to indicate readiness for birth of the foal. Keep in mind that maiden mares may not bag up until very shortly before giving birth. Some less common methods for detecting the onset of labour in mares is relaxation and elongation of the vulva and softening of the ligaments around the tail head. Work with your veterinarian to develop a monitoring plan to help to predict the occurrence of foaling.

When to Intervene

The expulsion of the foal is usually a quick process and occurs 15-20 minutes after the water (amniotic sac) breaks. If no progress is being made more than 30 minutes after the onset of labour, an intervention may need to be applied and your veterinarian or a trained attendant should examine the mare using good hygiene practices to ensure there are no abnormalities. After the foal is delivered the placenta should be expelled within 1-3 hours. If the placenta has not passed after 3 hours, call your veterinarian, as a retained placenta can lead to uterine infections and laminitis.

Colostrum Management

Foals are born immunologically naive at birth, meaning they have not developed an immune system to fight infection prior to being born. As a result, foals rely on the ingestion of good quality colostrum very shortly after birth to help acquire immunity from the mare, which helps them to prevent infections from occurring in the neonatal period. This is why it’s so critical that foals receive colostrum from the mare quickly following foaling.

For more information on improving foal immunity, check out the Decrease Susceptibility and Increase Immunity to Reduce Disease section of the Antimicrobial Stewardship in the Ontario Equine Industry FAAST Review.

What to Watch For

Ensure the foal stands and nurses quickly after birth, usually occurs within 30 minutes to 2 hours, as delayed nursing will increase the risk of failed transfer of passive immunity (where the immunoglobulins (disease-fighting cells) ingested from drinking colostrum are not readily absorbed by the gut for use in the immune system).

If the foal has not nursed in 3 hours, it may be too weak and in need of assistance to ingest adequate colostrum. To ensure that the foal receives high-quality colostrum, the mare’s colostrum can be tested using a Brix refractometer, where colostrum is classified as higher quality when measured as > 23%3. If colostrum is found to be of poor quality, the foal should be supplemented, ideally with a nipple bottle, with 500 mL of good quality donor colostrum prior to sucking from their dam.

How Much is Enough?

To ensure that the foal received enough protective immunoglobulins from the colostrum, it is important to test serum immunoglobulin levels 24 hours following birth. To test this, a blood sample is taken and using lab testing or on-farm Brix and optical refractometers. This helps to measure whether the foal transfer of passive immunity (or transfer of antibodies from dam to foal) has occurred.

The main levels to consider are4,5:

|

Serum IgG < 4 g/L (< 7.8% on Brix refractometer or < 42 g/L on optical refractometer) |

|

|

Serum IgG between 4 and 8 g/L (< 7.8% on Brix refractometer or between 42 to 44 g/L on optical refractometer) |

|

|

Serum IgG > 8 g/L (> 7.9% on Brix refractometer or > 44 g/L on optical refractometer) |

|

Source: Horse Journals

To learn about common diseases affecting horses, and pneumonia in foals in particular, visit the

Antimicrobial Stewardship in the Ontario Equine Industry FAAST Review

Preventing Meconium Impactions

The meconium or ‘first feces’ should be passed by the foal within the first 8-12 hours after birth. If the foal fails to pass the meconium by 12 hours, it is considered to have a meconium impaction, where the foal could experience abdominal pain (straining, tail flagging), depression, and be reluctant to nurse. If foals have not passed their meconium, an enema (as instructed by your veterinarian, and as part of your foaling plan) should be given through a soft flexible catheter. If the administration of 1-2 enemas does not resolve the impaction, contact your veterinarian.

Umbilical Management

Umbilical infections can be common in foals. Taking measures to limit their occurrence will lead to a healthy foal. To prevent umbilical infections, it is critical to consider environmental cleanliness. Good environmental hygiene of the area where foaling occurs, and the area where the foal and mare will be housed shortly after foaling.

Do not break or tear the umbilicus after delivery. Let this occur on its own, and if it does not occur, contact your veterinarian for instruction. It is not advised to band or tie the umbilicus.

Disinfection

The foal’s umbilicus is open for bacteria to enter shortly after birth, and therefore should be kept as clean as possible. Umbilical disinfection with 0.5% chlorhexidine has been shown to reduce bacterial levels on the umbilical cord shortly after birth6 and is less irritating than iodine. The disinfectant should be applied at birth and 2-3 times over the first 24 hours.

Links to Colostrum

The importance of colostrum management on the prevention of umbilical infections should also not be understated. High levels of immunoglobulins in the blood after ingestion of colostrum will help to fight bacteria that may enter through the open umbilicus.

For more information on environmental hygiene and biosecurity in broodmare barns, visit the Antimicrobial Stewardship in the Ontario Equine Industry’s Facility Management, Infection Prevention and Control, and Increase Immunity section

Neonatal Maladjustment Syndrome

Neonatal maladjustment syndrome (or dummy foal syndrome) is a common disorder where foals have:

- Reduced awareness of the environment

- Difficulty finding the udder and suckling

- Lack of affinity to the mare

Neonatal maladjustment syndrome is not typically considered an infectious disease. There is not enough evidence or research at this time to determine the main causes, but it is thought to be caused (at least in part) by impaired blood and/or oxygen flow and hormonal imbalances. Dummy foal syndrome can occur in both normal and abnormal births and symptoms can appear very soon after or take several days to develop. Treatment is typically dependent on the symptoms that appear.

It is important to note that while the cause of dummy foal syndrome is not entirely clear, it may occur as a result of sepsis (infection in the blood). Sepsis is often a result of poor antibody transfer when the foal does not nurse or does not receive adequate colostrum.

In more severe cases, foals may have a(n):

- Inability to regulate body temperature

- Compromised organ function

- Reduced intestinal motility

The Squeeze Procedure

A new technique has been found to manage this syndrome using mid-body compression squeeze pressure using a rope for 20 minutes7. It has been revealed that when using this technique, faster recovery of some foals diagnosed with this syndrome occurred, where it led to improved foal-mare interactions and minimized health problems. Work with your veterinarian to learn how this technique works and how to apply it properly.

Source: EquiManagement

Take Home Messages

- To improve the health and welfare of foals, management starts even prior to their birth through ensuring proper nutrition of the mare

- At birth, it is important to prevent complications in the birthing process and get the foal consuming high-quality colostrum as soon as possible

- Having a clean environment for foaling will help to protect against umbilical infections and other diseases

- Work with your veterinarian to develop a foal management strategy on your farm

References

- Peugnet, P., M. Robles, L. Wimel, A. Tirade, and P. Chavatte-Palmer. 2016. Management of the pregnant mare and long-term consequences on the offspring. Theriogenology. 86:99-109.

- Sheoran, A.S., S.S. Karzenski, J.W. Whalen, M.V. Crisman, D.G. Powell, and J.F. Timoney. 2000. Prepartum equine rotavirus vaccination inducing strong specific IgG in mammary secretions. Vet Rec. 146:672-673.

- Schneider, F., and A. Wehrend. 2019. Quality assessment of bovine and equine colostrum – An overview. Schweizer Archiv fur Tierheilkunde.

- Elsohaby, I, C.B. Riley, and J.T. McClure. 2018. Usefulness of digital and optical refractometers for the diagnosis of failure of transfer of passive immunity in neonatal foals. Equine Veterinary Journal. 51.

- Acworth, N.R.J. 2003. The healthy neonatal foal: Routine examinations and preventative medicine. Equine Vet Educ. 15:207-211.

- Lavan, R.P., J.E. Madigan, R. Walker, and N. Muller. 1995. Effects of disinfectant treatments on the bacterial flora of the umbilicus of neonatal foals. Biology of Reproduction. 52:77-85.

- Aleman, M., K.M. Weich, and J.E. Madigan. 2017. Survey of veterinarians using a novel physical compression squeeze procedure in the management of neonatal maladjustment syndrome in foals. Animals. 7:69.